Hip Hop and the Evolution of Muslim Culture

“Culture is uncontrollable. That’s why people like to define it from the outside.”

ASAD ALI JAFRI is a prolific cultural producer and community builder. Urban festivals, hip-hop cyphers, artist residencies – you name it, he’s done it! He brings creators together to imagine a more inclusive global Muslim culture. When he’s not spinning turntables as DJ Man-O-Wax or catching red-eyes like a true #digitalnomad, Asad curates programs at the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture, and Design in Hawaii.

I met Asad at a talk he hosted in Penang on his Creative Community Malaysia Tour. I decided to show up after stumbling upon the Facebook event with no clue what a “cultural producer” or “global Muslim culture” was. And the stars aligned: Asad has an incredibly wise perspective on identity, and we both had delayed flights to Kuala Lumpur the next morning!

Straight from the airport terminal, here’s a deep dive into Asad’s journey from confused Third Culture Kid to seasoned culture creator.

Let's take it from the top – but I won't ask, "Where are you from?" Your roots defy that question!

I was born in Kuwait. My father was born and raised in India, then moved to the U.S. in the 60’s for education and became a U.S. citizen. My mom was born in Karachi, Pakistan, to a family that migrated from India. When my parents got married, they moved to the U.S., then Nigeria, and then Kuwait, where I just happened to be born. I had an American passport as soon as I came out of the womb.

So I’m able to do this work because I was born in a country that wasn’t my own. I moved to a country that I didn’t feel was my own. My “homeland” sometimes feels like my own, sometimes doesn’t. My “community” or my “tribe” is really scattered throughout the globe. I feel like I can be at home anywhere and everywhere, but I’m also never at home. I think about how connection to the land is really important in indigenous communities, and I wonder if I can ever feel that.

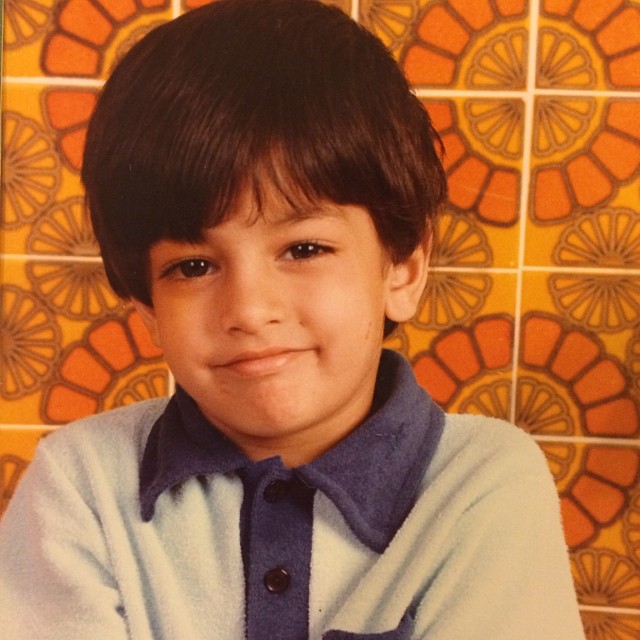

Asad, age 4.

How did your younger self make sense of this rootlessness?

It was really confusing. I thought being American was “cool,” as if it had some cultural cachet. Pakistanis and Indians weren't looked highly upon in Kuwait, so I definitely knew the subcontinent wasn’t cool. But when I'd tell the kids in my compound that I was American, they’d whisper, “He’s not American. Look at him! How can he be American?” But I could never be Kuwaiti, because you’re not allowed to be a Kuwaiti citizen unless you’re “really really from there,” whatever that means.

At the age of ten, I moved to the U.S. because of the first Gulf War. People always asked, "How do you not have an accent?" or “How do you know English?” I’d tell them, “Actually, my grandma teaches English in Pakistan. Don’t you know that Kuwait was colonized by the British? We grew up speaking Urdu and English, not just because I have an American passport." But most kids in school didn’t know what Kuwait was. People were generally confused, and that made me more confused. Until I came across hip-hop culture.

How did hip-hop culture speak to you?

As soon as I started listening to countercultural, anti-establishment, revolutionary music, like Public Enemy's Fear of A Black Planet, I connected immediately. Although I lived in the suburbs of Chicago at that time, the schools I went to were diverse in race and ethnicity, mostly lower-middle income. At an early age, I was also reading things like The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Slowly, I became attracted to black culture because I could relate as the Other.

But the distance from my actual identity was still huge. I couldn’t pass for black, but people often thought I was Latino – and I thought it was cool. My brother and I started shaving our heads into a bald fade and lining up our beards so we had the look. People really thought we were members of Latin King or hip-hoppers from New York, and we wouldn’t go out of our way to correct them.

In your talk, you said, “You can’t build community until you know yourself.” What strengthened your identity and connection to Muslim culture?

You can't talk about Muslim culture in the U.S. without talking about black culture. The 1992 movie Malcolm X made being Muslim "cool" because black and Muslim culture were countercultural. Way back when I was into [Malcolm] X hats and Wu-Tang Clan, I wish a movie like Black Panther had come out. Within five minutes of watching it, I was in tears because I really related to it. The hip-hop and martial arts influences – things like this really helped me back then. Black Panther talks about agency over your identity, something that many of us are looking for. I had to learn to love myself and my people and my identity, in order to help other people.

The movie also talks about Afrofuturism. I like this idea of Islamic, native, and indigenous futurisms. It allows us to explore and dream. As Muslims, we often live in the past, and that's problematic. When we talk about culture and social justice and writing our narratives, it's not just about the current, it's also about seven generations down the line.

How has your family passed on Muslim culture to you?

My father being one of twelve, we have a huge family network! When we first came to the US, we didn’t have anywhere to stay. We didn’t know what was happening with our finances because of the war. So my six-person family stayed with our cousins, two single bachelors in their twenties. I remember sleeping in the basement and, you know, doing the immigrant thing. Everybody in one house. Because of those experiences, culture gets passed on naturally.

My parents would speak to us in both languages. They would make food and listen to spiritual music from the subcontinent. Relatives would host religious gatherings. My uncle has a spiritual center in his basement. Even though he's the youngest brother, he’s the spiritual go-to, say, when my mom needs somebody to pray for her. She's also reading the poetry of my great-grandfather. He wrote love poetry and spiritual poetry, so my mom recites it a lot. I would love to carry on that tradition.

How does your family stay connected nowadays?

My mom’s side is super cosmopolitan. They work for the UN, they’re journalists, they’re ambassadors, and they’re all over the world. So I can connect with them really quickly and have conversations like this all the time. But they’ve never been based in one place. They’re always moving around.

My father’s side comes together for reunions when all the kids get married. I know a lot of people hate them, but I really like the wedding rituals. Many come from Indian culture, but they’ve become syncretic and transformed. A famous tradition in all Indian-Pakistani weddings is that the groom’s shoes will be stolen until he pays the sisters or cousins of the bride. The public negotiation is the really fun part: “You think our sister is worth just $100?! We want $10,000!” You hear about these epic weddings in Bollywood, and the truth is, they’re really like that!

No matter where you are in a diaspora, when a wedding happens, you try to hold onto the things you remember from a different generation. My aunts and uncles who are really, for lack of a better term, “fobby” – they know this world. But I don’t know if their kids will, unless they pass it on. So I’m really interested in keeping those traditions alive. They come out at big life moments like birth and death, not necessarily on a day-to-day basis.

What sparked your passion for amplifying global Muslim culture?

Several years ago, I learned about communities of young people around the globe, usually in cosmopolitan cities, who identify as Muslim creators and cultural producers. Their Muslim identity is not purely religious. It’s the social and creative communities they belong to. It’s their political identity. It’s geographic, regional, even diasporic. Between Chicago and New York, Karachi and Lahore, Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta, Cape Town and Durban, London and Birmingham, Berlin and Brussels, and so on, I saw an emergence and renaissance of global Muslim culture.

Why is this happening now? Partly because time evolves things, and partly as a reaction. Wherever you are in the world, you understand that there’s an ongoing fight about what it means to be Muslim. Not just where Muslims are a minority, but also where Muslims are a majority. Any marginalized people can overplay the role of the victim, at the expense of addressing real systematic issues within our own community. As Muslims, where is our internal conversation about privilege? I want to see Muslim leadership that’s majority women, black and Latino, non-Sunni.

But sometimes, a small minority within the majority wants to define the dominant narrative for everybody else, like religious and political leaders. Muslim spirituality is often tied to a specific sect, ethnicity, and language. When I connect beyond those labels, like if I'm playing Tinariwen with electric guitars from the Malian Desert, that can be super foreign and not seen as part of a bigger Muslim culture. People often have to see themselves in it consistently, in order to connect to it.

So I say “global Muslim culture” because it’s subversive. It includes cultural leaders, and if you can gather them, you include everybody. Our vision is to create a network of people, collectives that can share resources, learn together, and come together when needed. We’re taking on a revolutionary model that says everything is open-source, including our art. That’s dangerous and scary to some people, but I think we’re in a time where we have to take ownership as a community.

“Calligraffiti” mural by eL Seed, a French-Tunisian artist who Asad invited for a 2016 INTERSECTIONS project at the University of Houston.

Asad on tour as Artistic Director and DJ with Arts Midwest's Caravanserai.

Given the diversity of ways to identify as a Muslim, how do you activate – and inevitably define – a global Muslim community that, in its very nuance, resists being defined? How do you invite people to "be part” of a community, even if it's more inclusive, without perpetuating language and expectations that may draw lines between insiders and outsiders?

Really important questions. I used to worry about this a lot. Who belongs? Who doesn’t? Do you label it? Do you not label it? Do you even call it Muslim or not? What does it mean to redefine, reclaim, and have agency over your own identity?

It gets problematic because “identifying as Muslim" in itself is a box that shouldn’t exist. In a Muslim-majority country, Muslim is often not the counter-culture or the anti-establishment. It is the establishment. But when I say Muslim as a label, people build a box around a specific idea that’s different from the lived experience. For a lot of people too, their Muslim identity is shaky. And I’m not the type of person who only wants to work with Muslims, right? There's always been people who don’t necessarily identify who have been part of the movement.

So we define it as broadly as possible. At the base level, if you want to be part of this movement, we don’t need anything more than you saying that you’re just a Muslim. And even if you’re not, you are welcome. We value social justice and creating in connection to the sacred. And what’s sacred to you is different, right? We’re not going to test your Muslim-ness in any way. We use words like "Muslim-ness” intentionally, so that even if you don’t feel fully Muslim, just Muslim-y, that’s okay. We value what you value, and we see you for what you see in yourself.

You've often said, “Culture is uncontrollable.” How have you learned to “let go” as you build a movement much bigger than yourself?

Cultural producers create the stuff we believe is needed to fill a gap or void in the world, and then the right audience naturally finds it. That’s the power of story, art, and culture. You don’t have to over-define it. When people look back 10-15 years from now, everything they see – that’s your work, right? Everything you do, like this series, doesn’t have to encompass everything you want to say. I used to be like, “Everything needs to have this, this, this, and this.” Now I’m just like, “You know what? People can figure it out. Eventually.” It's completely alternative to a marketing model, where you look at numbers and profiles of people. At some point, you just have to trust the process.

Gathering people – that’s the real work for me. Building relationships is building community, and for that I don’t need so many definitions. Nowadays I just say, “Hey, connect! And you’ll know why.” They make the magic happen. You don’t have to control that process. You don't have to affect billions, millions, or thousands of people. Just make sure people are coming together. Work in those communities you know, and start building something that starts redefining culture, even if it’s generations down the line.

So to create culture, you create community.

That's right. Culture is an ecosystem. It's not bound by time, space, or place. It evolves with a community that’s not easily defined. People come in and out, and intersect through different lenses. Eventually, they start to see the spectrum of the conversation, beyond a single channel. Eventually, the community defines itself. And once the community is together, the definitions don’t matter as much anymore. Culture is uncontrollable. That's why people love defining it from the outside. Yet it's community that responds to it, and community who evolves it.

Caravanserai: American Voices hip-hop workshop with students in Traverse City, Michigan (April 2016).