Two-Legged Therapy

“The biggest block is often the mental block of 'I’m lesser than.’”

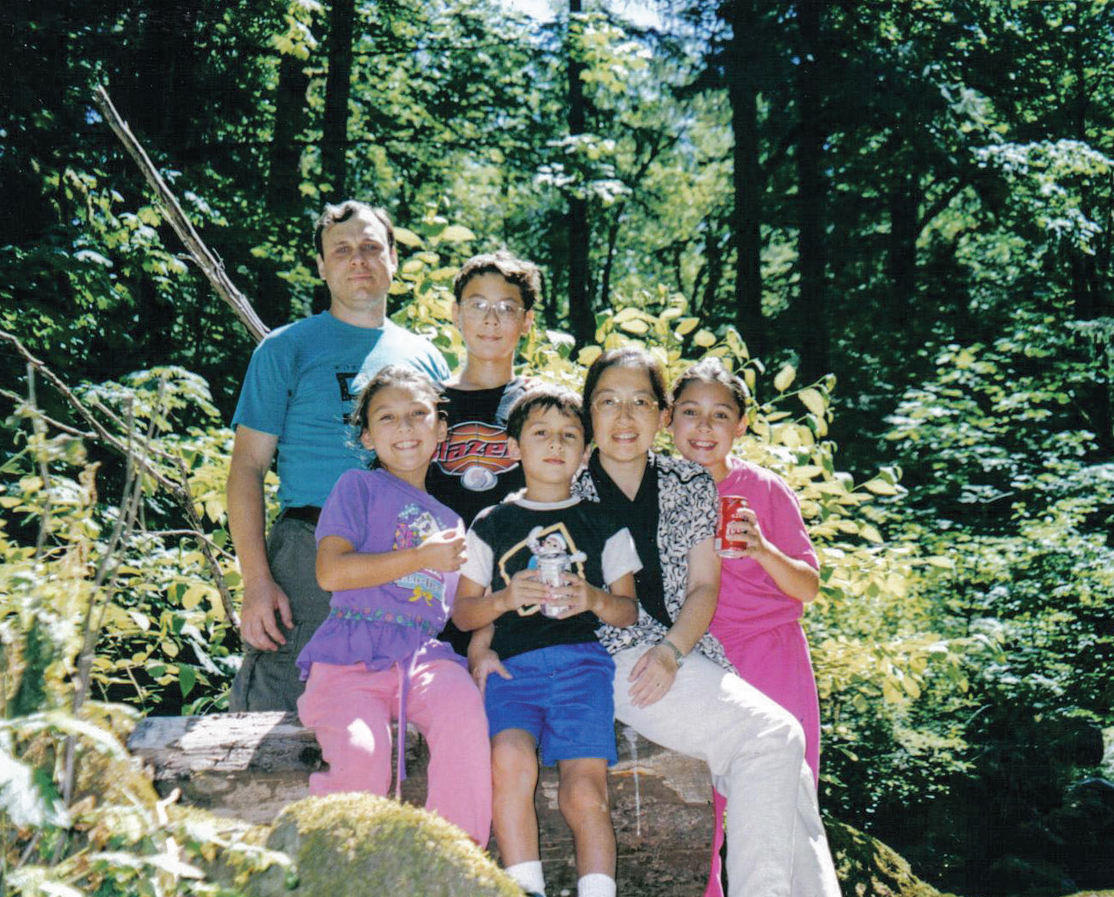

MICHAEL RAU & LINDA VALERA run on two “cultural legs.” Born to a Taiwanese mother and American father, the siblings have undertaken “rehabilitation” from lifelong pressures to exercise not only one, but every fiber of their multiethnic identities!

I originally planned to just interview Linda, an international school teacher who leads a Spanish-speaking community in Beijing with her Venezuelan husband, Romer. However, as Michael happened to be in town, she brought him and Romer along for a rich analysis of the pains and gains of cross-cultural self-therapy.

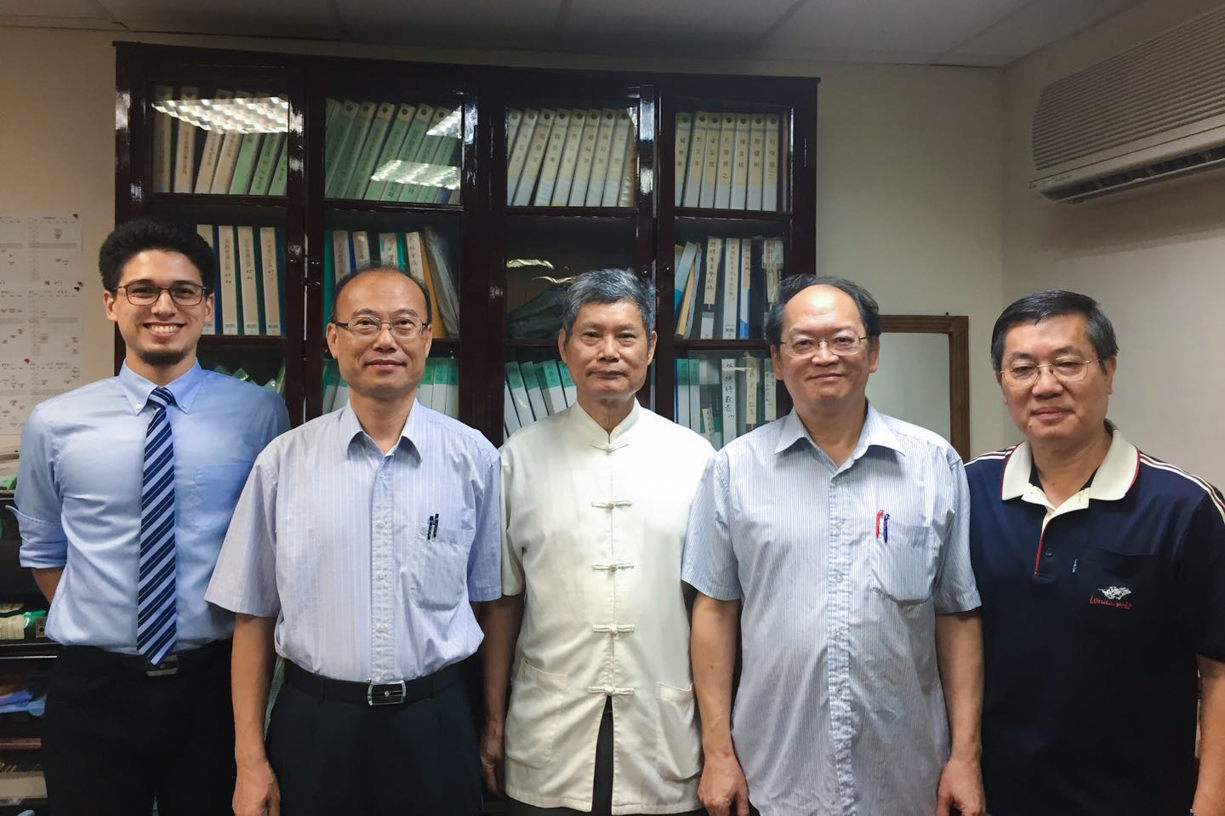

Eye-opening for my own language learning, this #ChrysalisConvo explores the motivations behind Michael’s marathon leap to the root of Chinese culture – that is, Chinese philosophy. The last three years have seen his return to Taiwan for a Masters in Chinese Philosophy at National Taiwan University. Flexing some major Mandarin muscles, he recently completed his thesis (fully in Chinese!) on Mencius and metaphors and is now pursuing a Ph.D. in Chinese philosophy focusing on Zhuangzi (庄子).

Enjoy Michael’s “rehab report,” and stay tuned for part two with Linda and Romer on their multicultural wedding!

Let’s break down the metaphor. What does physical therapy have to do with “cultural rehabilitation”?

MICHAEL R.: I was born with two legs: one Chinese language and culture, one English language and Western culture. Most of my life was spent using and strengthening one of them, whereas the other one was, from lack of use and training, atrophied. By the time I hit my senior year in college, I thought, “Well, I could continue to just let it be, or I could try and go back to Taiwan and study something I’m already interested in, but in Chinese.” So the past three years I've been in Taiwan, basically doing linguistic and cultural therapy on my atrophied leg. Especially with physical therapy, the biggest block is often the mental block. It’s not the physical strength that you have to get back that’s the most difficult part. It’s the mental block of “I’m lesser than” in some way, or “I’m somehow deficient.”

Growing up, what environments shaped each “leg”?

MR: I grew up in an international school system in Taiwan through middle school. So, English-based education. In sixth grade, I started learning Chinese reading and writing. After three years, I went to high school in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for a year, where I continued to study Chinese independently with my mom through a community resource program there. I spent most of my time with Asians or Asian-Americans, many of whom went to Chinese school. Then we moved to Wheaton, Illinois. That was a tough transition, like “mustard land” to "mayonnaise land”: very yellow to very white. Then I went to Wheaton College, where I double majored in Western Philosophy and Bible & Theology.

LINDA V.: Mine was a little different. My whole education was in Taiwan, except ninth grade at a public school in Minnesota. My parents said, “You need to go to a public school before you go off to college. You look American, white American – but you don’t know what it means to be American!” It was quite hard that year. I thought it would be easier, but our vision of America was just based on vacation. Cultural stereotypes also rubbed off on me, like “Americans are all stupid. The Asians are the smart ones.” So I distanced myself from everybody, until I found people who didn’t fit the stereotype. Then I went to Michigan State. Even though the university was huge – around 43,000 students, and I came from a graduating class of ten – that one year in the U.S. was really helpful for me to just hit the ground running. I already knew, “I’m not going into stereotypes. I’m just going to meet people, and I know that they’re just awesome.”

Did your parents consider immersing you in local Taiwanese education?

LV: Our parents really wanted to keep us in the local schools.

MR: But it didn’t work. Our dad taught at an international school, where he saw the model of what they wanted to do: kids learn at a Taiwanese school through grade six, then transfer to the international school in grade seven. Ideally, you think they’ll have both languages. What ended up happening for all those kids, without exception, is that they would be really bad at English for a long time… and then they’d lose all their Chinese.

LV: Our older brother was actually the first one to go to a local Taiwanese school. No matter what he did, they always considered him a foreigner. Because of the way we look, we have to be completely literate in English. Even the little kids would ask him, “Hey, can you help me with my English?” He’d be like, “I’m sorry, my English is as good as yours. I don’t know any more or less than you do.” So my parents realized that we needed to be fluent in English, and they gave up the Chinese in order for us to strengthen that English leg.

Depending on where I am, it’s easy to feel “too American” or “not American enough.” I certainly feel more Malaysian outside of Malaysia. Now, I’m rewiring how I feel being Chinese in China, which is reshaping how Chinese I feel outside of China.

How Taiwanese and American do you feel around the world?

MR: In the Taiwanese context, my American side is suppressed. I don’t know how to articulate it in a way that is understandable or communicable. Yet in the US it’s the flip side, where I don’t have any opportunities to speak Chinese. Taiwan becomes this idyllic, idealized place. Then you go back, and you’re like, “Ok, not as idealized as I remember.” So it doesn’t matter where you go – there is always a sense of incompleteness. Almost as if you’re forced to hop on one leg, and there's no place to put your other leg. It’s just dangling here like deadweight, and you feel the weight dragging always in the back of your mind. So I think there is a universal feeling of “lost-ness” that is probably true of every human being, if they’re fully honest with themselves. People who grow up cross-culturally or internationally just feel it more acutely. They’re not as easily deluded into the sense of “I completely belong here” because it’s an inescapable fact of life.

LV: My first year in college, most friends on my floor were white American. At one point, I actually forgot that I was Taiwanese. Until I went back to Taiwan. “Oh yeah! This is part of me too.” It was weird. I’d never felt that way before. Back in Taiwan, people would say “外国人, 外国人 [wài guó rén: foreigner],” and you’re like, “No! I’m not a 外国人. I am Taiwanese!” To then have such an extreme switch was very, very humbling for me. No wonder some Chinese Americans don’t feel Chinese, you know? I was there one year, and I already felt like I’m American, not Taiwanese at all. But then I started hanging out with more international students, and that’s when some of the rehabilitation happened.

Linda, has living in China strengthened or plateaued your Taiwanese leg?

LV: I like being in China as a Taiwanese American– or as American– I don’t– anyway– well because– (breaks off, laughing)

MR: That's interesting that you don’t know what to call yourself.

LV: “Taiwanese American,” I normally think of a Taiwanese person who’s grown up in America. So I’m not Taiwanese American. But American Taiwanese is not really a term.

MR: I say Taiwanese. Now. With an asterisk. Depending on the situation.

LV: Which is why right now, I don’t really know what to say. We’re on a middle ground.

MR: It’s like we’re creating a neutral space, or a collective space.

LV: Actually, being in China has really helped me to gain a footing in terms of who I am. Because here people can call me a 外国人 and I don’t feel offended by it. In Taiwan, I would get mad. But in China, I am a foreigner, you know? I’m not from China. I’m American. I’m Taiwanese. I am still ethnically Chinese, and I can say to them, “I am Chinese.” So I feel completely comfortable calling myself Chinese and Taiwanese, and people here are completely okay with me being Chinese and Taiwanese and American.

MR: In Taiwan, when people would call our brother a foreigner, he would reply in Chinese, “Yeah, I’m a foreigner. So what?” and scare the living daylights out of the little kids. I would always laugh really hard, like “I want to do that too!” then be too scared to do it in real life.

LV: Several times when they’ve said "外国人! 外国人!” to us, we’re like (pointing right back) “中国人! 中国人! [zhōng guó rén: Chinese person]” and they’re like, “Gasp!” They don’t expect it.

MR: Shovel it right back!

LV: Especially with kids, it gives the parents a 台阶下 [tái jiē xià: a way out from an awkward situation].

Michael, what mental blocks has your return to Taiwan helped you overcome?

MR: It’s helped me understand our mom more. Growing up, there was a huge cultural and linguistic gap between the four of us kids and her. She always had to dumb down her language to talk to us. She was very studious and often said 四字成语 [sì zì chéng yǔ: four-character idioms] drawn from the ancient texts. But now she's said, “I feel like I finally don’t have to filter my language.”

As for mental blocks, I had to have my mom. When I first mentioned, “Oh, maybe I should go to Taiwan,” it was half-jokingly. I wanted someone to tell me, “You can do this,” and be that 靠山 [kaò shān]: someone able to help me be confident when I’m not confident, to see things I’m not able to see from my vantage point. I actually first wrote the [leg therapy] metaphor in my journal. I didn’t realize how significant it was until I talked with her, and she was like, “That’s a really good metaphor!” When it’s echoed back to you, you realize it captures the experience of trying to reclaim something you’ve been born with but haven’t been able to display with the confidence that you would like. So she encouraged me a lot, and I just thought, “If my mom was able to go to the U.S. and learn English, I should be able to go back to Taiwan and learn Chinese. Yes, I’m really scared, but I want to be courageous about it. Even if other people don’t think I’m at a certain level, I have to have enough confidence in where I’m at, because only I know where I’ve come from."

Indeed, we’re all “running our own race.” How have you grown in choosing courage over fear?

MR: When you have an atrophied leg, you feel like everyone else knows everything, when in fact they probably just know 80% and that’s functional. When they don’t know, they ask, but they don’t feel this crushing weight of insecurity when they ask. They’re like, “I feel comfortable. This is my language. This is my culture.” But for people learning as a second language, it’s easy to feel like every single question is a revealing of that atrophied leg. You remember it as it was dry and shriveled before, even though now it’s a lot stronger than you think, and people might not even be projecting onto you, “Your Chinese sucks.” They’re like, “Oh, that’s a good question!” Whereas you, you’re the only one who’s thinking, “Is my Chinese identity at stake? Is it up for trial now?”

LV: We grew up going to a traditional Taiwanese church. In Bible study, we would go around in a circle and have to read the Bible out loud. I hated it. I would feel like such a dork, like I’m Taiwanese, but you all see me as a foreigner because I can’t even read the language.

MR: There tended to be two options, both of which weren’t good. Either they just skipped over you, which is symbolic, like you're literally not part of the conversation. Or every single word had to be read to me. I hated it every time. It was another affirmation, at church, of your Otherness: “You don’t completely belong in this family.” So after I went back to Taiwan, I’d read ahead, like “1, 2, 3, 4… Shoot! I can’t read verse 4. How am I going to respond? Am I going to pretend like I know it? Am I going to ask for help? Or glaze over it, like "Oh yeah, sorry, I skipped a word”?

LV: SO STRESSFUL!

MR: But this time, I made a conscious effort to ask, “What is this word?” They said it, then I said it. And kept going. My heart was beating like crazy. And then at the end, I shared, "You know, that was really hard for me. I really hate not knowing, and I feel insecure about asking.” Turns out, they didn’t actually see me as a foreigner, and in the ensuing years, a lot of them would actually defend me! If someone said, “Oh, so you’re a foreigner?” they'd be like “No! This dude is more Taiwanese than you are. Get in line!” When that happens, I feel this warm fuzzy feeling. They’re my friends, and they’re speaking on my behalf because they know where I come from and what all this means to me.

Any advice for folks interested in linguistic and cultural rehabilitation?

MR: Our goals are often too hazy. I once asked a guy, "How good do you want your Chinese to get?” He said, "I want to be able to understand everything people are saying in Chinese small group.” I was like, “I don’t even understand everything people say in Chinese small group. Most Chinese don’t even understand. Why? Because a lot of it is technical language.” You don’t realize that even native speakers don’t understand everything. If I was to measure myself – and I’ve done this a lot – against my professor, who’s a master in Chinese philosophy – it’s just unrealistic. I have to have very concrete goals, and be realistic about what I can and can’t attain, as well as where other people are at. They have their holes too. I want to know where my holes are, so that I can improve and always be getting better. What are you training for? Are you training to run an Olympic race in Chinese? If you’re not, then don’t worry about having an Olympic leg! Only a tiny fraction of people have that. As long as they can walk, maybe jog, and they’re healthy, that’s all they need. But it’s hard to see that when you feel like you’re at the bottom. So it’s important to guard against insecurity. Otherwise, it’s really easy to spiral, and put this weight and pressure on yourself that you can’t crawl out from under. I’ve gotten to a point where I’m more okay with not knowing sometimes.

A successfully defended Masters among masters!

Tell us about your Masters thesis on Mencius and metaphors. How has studying Chinese philosophy shaped your view of Chinese culture?

MR: Mencius was the ideological successor of Confucius. If you want to understand the foundation of Confucian tradition, you have to understand 孟子 (Mèng Zǐ). If you just work on Confucius, the materials are actually really sparse. Metaphor research is not huge among Chinese philosophers, whereas in the West, it’s much more of a thing among Sinologists, who intuitively understand, “This is our way in.” Metaphors act as a bridge between cultures. You’re able to understand even if you don't understand definitions like traditional speakers might. So I was answering a Chinese question with Western methodology: “Why was Mencius so argumentative?” A lot of people nowadays think, “He just liked criticizing people! That’s all he was good for.” My research found that there was a systematic nature to it, and I tried to articulate what his rationale was, so that in every single instance you would know the kinds of people he would criticize and why. There’s so much from Mencius, it’s mind-boggling. You just can’t get away from him. Many people quote him, and they don’t even know. 浩然之气 [hào rán zhī qì: limitless source of moral force, a “flood-like qi”], even values like 仁义礼智 [rén yì lǐ zhì: “four principles” of benevolence, righteousness, etiquette, and wisdom].

ROMER V.: 喝热水 [hē rè shuǐ: drink hot water], 休息 [xiū xi: rest]!

MR: Except that!

LV: It’s funny though – today when you visited my school and saw all those posters on the wall, you kept making connections. I’ve been there for three years, and I've never looked at them. I just walk by them.

MR: The posters detailed school values, like responsibility. All from 论语 (Lún Yǔ), the Analects from the Confucian tradition. All stuff I’ve read in the past three years. When I saw it, I was like, “I know where that’s from. I know what that means. They're trying to tap into Chinese culture at the root.” Today I see Chinese philosophy undergirding a lot of what the Chinese government is trying to push again. After the Cultural Revolution, there was this huge cultural vacuum. What do we fill it with? It’s nothing so far, just capitalism, which is only money on the surface. You have to have a driving value system to fill the vacuum. A lot of super successful businesspeople reach a certain degree of success and they’re like, “It’s empty. What now?” and they go to classes on the Classics taught by my professor, who charges bank and makes bank because people want that. They need it. They sense that it’s not enough to just be really, really successful monetarily. So I’m trying to be intentionally connected to Chinese culture, going straight to the core, the foundation, the root, of what it means to be Chinese. I want to figure that out. Because I can’t just go by phenotype or schooling. I’ve got to go somewhere deeper to find that connection. And as a result, it’s made my roots deeper.

What’s next? Do you have a longer road in mind, leading back or away from Taiwan?

MR: I’m not sure. The goal is to teach and do research eventually. If you’ve been hopping on one leg your whole life, and all of a sudden you’ve strengthened your other leg, and now you’re walking on two legs – all your muscles have to adjust and re-harmonize. Your whole sense of equilibrium is shifted. Your center of balance is different now. Every step is like “ooh, ooh, ooh.” You’re very sensitive to the feeling.

LV: And I was always just a little bit scared, “Is it going to fail me?”

MR: Is it strong enough? Should I be competing in the academic Olympics in Chinese? Or is there a way that, like Linda, I can find a job in a place that’s best suited to all of my talents, so that I’m not competing on somebody else’s turf or territory? A Chinese-American acquaintance of mine wanted to teach in a local school in Taiwan. I was like, “You’re not playing to your strengths. With your background, if you teach at a local school, you’ll be behind everyone. But if you go to an international school, you’re coveted in both areas. Your Chinese is better than all the foreigners, and English is your first language. You’d be able to bridge both worlds.” So, where is my niche? Where I’m straddling different worlds in a way that my training is best suited to have a greater contribution? Where I don’t have to hide, or compete unfairly, or always from behind? This is me trying to figure that out now.